In our last post, we gave you some background on the four core elements of the CMS Emergency Preparedness Regulations1 along with a few takeaways with the help of Direct Supply’s Director of Risk & Safety Solutions, Ray Miller. This post dives into the fourth pillar of those regulations, Training and Testing, with overviews and general tips related to community-based and tabletop exercises.

Community-Based Exercises

As the name suggests, this style of exercise involves stakeholders from your whole community (CMS encourages this in their interpretive guidelines). Different from a drill, which tests just a piece of your plan, a community-based exercise requires multiple agencies, mirrors real events and tests your entire EP plan.

Most of us realize that “the new emergency preparedness Final Rule is based primarily off of the hospital emergency preparedness Condition of Participation (CoP).”2 That said, local hospitals have been using this standard for some time. They have already completed their All-Hazards risk assessments, developed and implemented their plans, policies and procedures, and trained and tested accordingly.

As you begin to develop relationships and participate with your local healthcare community through community-based exercises, other providers, including hospitals, may want to know what your overall capabilities are. In order to respond appropriately, your plan, policies and procedures, training, and testing will need to align with the other care providers. As a specific example, the other providers may need to know what your receiving capacity and capabilities are in the event of a med-surge scenario.

Keep in mind that in order to actually fulfill the CMS requirement for a community-based exercise, you will need to be able to demonstrate/document your participation in the planning and implementation of a clinically relevant event. You will actually need to establish all components necessary to fulfill your defined/assigned role in the exercise. Be sure that this is clear in your documentation.

As common as it may be in the world of Senior Living, this is not the time to go (or stay) rogue and figure it out yourself. The coalitions and collaborations you establish and foster with community members like AHJs, first responders, other provider organizations and your Emergency Preparedness office/organization will pay enormous dividends in an emergency or disaster. This “pre-event” preparatory work will probably be some of the most important energy you expend. Think about the benefit of working together to share information, build and become part of the community response teams, and promote both internal and external situational awareness.

Tabletop Exercises

A tabletop exercise (TT) can be defined as a group discussion where participants meet to determine what they would do in an emergency situation. You can find help resources online3 about tabletop exercises, but, in a nutshell, here are the nine pieces you’ll need to include:

1. Pre-Planning:

- Identify an exercise planning team

- Develop an exercise timeline/milestones

- Establish a draft-planning meetings calendar

Do Residents Have to Be Included in the Exercises?

According to the CMS EP Interpretive Guidelines, your communication plan should have a method for sharing information from the emergency plan with residents, their families or representatives (such as a “Fact Sheet” or informational brochure). Surveyors may even interview residents and family members to see if this has been done.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and CMS provide a six-page emergency planning checklist for long-term care residents, their family members, friends, etc.

- Plan elements to be practiced, tested, evaluated, strengthened, etc.

- Determine participating departments, roles and job tasks (based on functions to be tested)

- Define the specific, realistic and clinically relevant hazard scenario(s) and exercise location

- Clarify job and emergency-response role functions that participants will practice during the TT

- An overarching, single-sentence statement of the exercise goals that focuses and directs the entire exercise

- It should a) enable the selection of objectives and b) clarify the exercise purpose

- For example: The purpose of this exercise is to test, coordinate and strengthen departmental and individual responses in the instance of a/an (e.g., loss of power, elopement, internal fire, specific severe weather-related event, etc.)

Whether you consider the exercise objectives to be the framework or the heart of the scenario, if they are well written and consistently adhered to, they will serve to guide the scenario development, the evaluation criteria and focus support on exercise priorities. As with other/most objective-writing undertakings, consider:

- Following the acronym SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-framed)

- Having a limited number of objectives

- Using them to maintain focus, meet timelines, guide scenario design and ensure successful completion of exercise goals

- Sample objective 1: Test day shift staff’s capability and capacity to evacuate residents externally

- Sample objective 2: Test the management team’s capability and capacity to respond to and re-plan due to significantly changing severe winter weather warnings and patterns (supply replenishment needs, staffing challenges, electrical grid outages, laundry shortages, etc.)

Effective scenarios can be laid out as “written narratives” or “event timelines.” As you develop your scenario, keep referring back to and align with your scope, purpose and objectives and avoid the temptation to write a “screenplay.” Be careful when using audio-visual and powerful images – these can quickly overshadow or even derail your TT. Your TT should be a) a team-building exercise, b) an EP plan-testing discussion and c) a decision-making experience.

Your tabletop exercise should also be based on the findings of your actual All Hazards Risk Assessment. It’s worth asking, “Could this actually happen here?” To be most effective, your TT scenario must be a) clinically relevant, b) real-world and c) CHALLENGING. Keep in mind though that while it should test your EP plan and the TT participants, your TT should not overwhelm them.

- What is the story line?

- How will participants meet the exercise objectives?

- What are the important scenario details, conditions and events (timeline, significant challenges and conditions, plan elements to be tested, etc.)?

As the facts of an actual event rollout are revealed, plans and responses will have to be modified or changed (both big and small). That is all part of the testing and the learning when conducting a TT exercise. In essence, your TT team will hone their skills in a simple but important process of monitoring, assessing, learning, modifying and communicating.

You will need to run your TT exercise in much the same way as a real event. That is the only way you will actually test both the EP plan and the TT participants. The goal of any properly designed and conducted TT is to create the scenario and the “scenario environment” that engages the participants and causes them to discuss and decide on realistic actions while learning from and teaching each other.

To accomplish this, you will need to develop a list of “changing scenario facts” that you will, as the exercise progresses, hand to the TT team (on a slip of paper or text/email/etc.) Things like: unplanned-for freeways closure, fuel shortages, stranded employees, generator failure, significantly lower temperatures, hurricane direction change, a 2nd/3rd hurricane, federal confiscation of your evacuation vans and buses, etc. How will your TT team respond? How quickly can they identify the impact, the needed plan modifications and any alternatives?

8. I.D. the Right Participants: Your first thoughts are to include your ED, DON, Dietary, Housekeeping, Laundry and Maintenance staff. But who else should attend and perhaps, who instead of? Thinking about who else is CRITICAL to the organization’s emergency management, security, inventory and purchasing, business continuity programs, institutional knowledge and experience.

“Just think of the institutional knowledge a longstanding CNA might offer,” says Ray. “They would know things that others simply could not. Together, you can conquer anything.”

9. Management:

To ensure tabletop exercises aren’t a lecture, establish roles to encourage participation and efficiency. Naturally, you’ll want a good scribe. But even more important here is the role of the facilitator, whose job isn’t to lead the conversation, but to get everyone involved. (At the same time, everyone should act as a facilitator, too.) As both a group discussion and brainstorm, your TT should generate ideas and a plan from which to develop over time. Assumptions, negative comments and judgments have no place in these meetings – be sure to reinforce that, if necessary.

As far as time commitment for tabletop exercises, expect preparation to take up to eight hours if done alone versus about just two hours if collaborating. The exercise itself should take two to three hours while the follow-up of an After Action Report and EP plan revisions may take up to four hours.

Because there are so many variables in an emergency, the first tabletop exercises may be somewhat challenging. But you’ll quickly master and learn to highly value them. When done right, they produce so many benefits and so many reality checks.

And please, use an After Action Report.

Ray’s Conclusion on Community-Based and

Tabletop Exercises

The fundamental themes here again involve the concept of pre-event. Whether you participate in a community-based or tabletop exercise, use the information you gather – and document – to revise your EP plan. A post-event “hot wash” discussion with those involved in the exercise is the perfect time to discuss what went well and what still needs to be done. If no actions are taken following an exercise, you’ve essentially wasted everyone’s time.

The bottom line is this: when prepared through training and testing, you’ll be empowered to respond (versus just react) appropriately in your various roles within your building, your immediate neighborhood, and even the broader community and beyond.

Ray Miller

Educator, Storyteller, Wanderer

BS, MSOSH, GP

Director of Risk & Safety Solutions, Direct Supply

If you have specific questions regarding the EP rule, email SCGEmergencyPrep@cms.hhs.gov

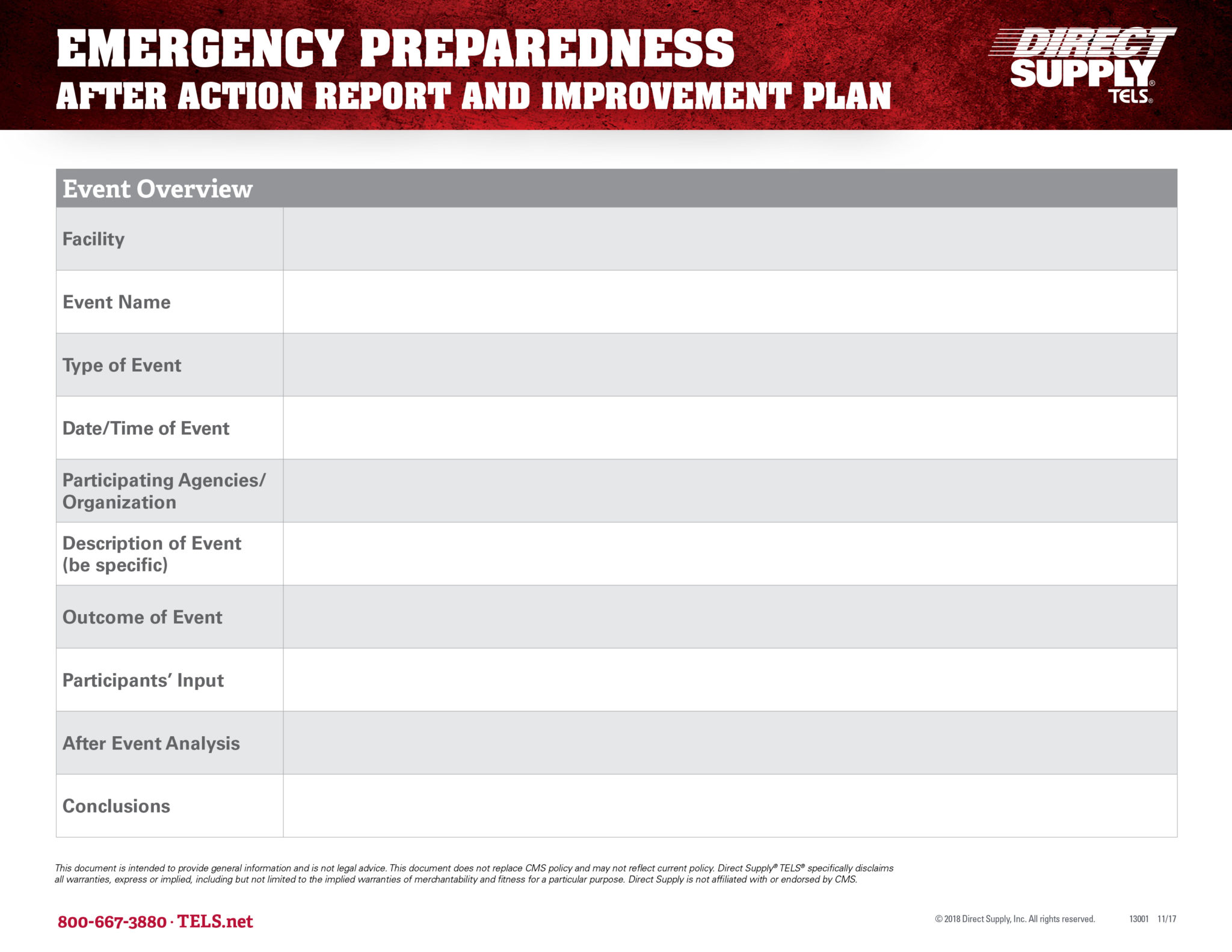

Direct Supply® TELS™ & After Action Reports

Following a real emergency or just an exercise or drill, providers should document the details of the event in what’s called an After Action Report. While CMS does provide a seven-page report for this, TELS Platform offers a simplified one-page version for its users (expandable, if needed). On this report, you’ll take note of participants, lessons learned, staff statements and more.

You can use TELS Platform to store emergency preparedness documentation, track routine compliance tasks and more. To sign up, visit TELS.net.

Download the TELS After Action Report.

1. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertEmergPrep/Downloads/Advanced-Copy-SOM-Appendix-Z-EP-IGs.pdf

3. http://go.everbridge.com/rs/004-QSK-624/images/10-step-model-incident-command-system-WP.pdf